The Silent Blocker: What Game Theory Taught Me About Infrastructure & Platform Engineering

Back in 2018, I started my studies in Game Development with a focus on Design. One of the first lectures that year covered the concept of Flow: a state of complete immersion and intense focus, often referred to as being "in the zone".

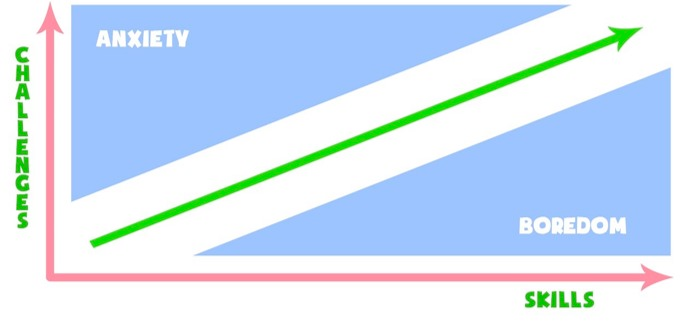

In our industry, a designer's job is to 'develop fun'. While fun covers a broad range of emotions, there is a universal agreement on how it breaks: when the balance between the challenge of an activity and the user's ability to meet that challenge is skewed, we are definitely not having fun.

While that lecture focused on the player, the logic applies equally to the creator. This article explores that parallel: tracing the concept of Flow from the game mechanics we design, through the development challenges we face, to the emerging role of Platform Engineering.

Flow in Games

Games are the perfect playground for reaching this flow state because, unlike the chaotic variables of the real world, game environments are closed systems specifically designed to induce it. The player is exposed to carefully curated obstacles meant to challenge them without overwhelming (or underwhelming!) their abilities.

Another unique aspect is the instant feedback loop. Think of Super Mario, for example: Hit an enemy? Instant death, signified by immediate sound and visuals. (Sidenote: I was very surprised when I found multiple 30+ minute "Mario death animation" compilations... the internet is weird.)

This rapid feedback allows for quicker 'iterations' in problem-solving. It creates a continuous cycle of Hypothesis → Action → Validation, sustaining immersion without ever breaking the user's focus. In essence, Game Developers design the entire experience around managing these "blocks"—knowing exactly when to remove friction to keep the player immersed, and when to introduce it to keep them engaged.

Flow in Game Development

Back in 2018, during my first year of "Game Design school", I realized that the "zone" isn't just for the people holding the controller. I remember sitting down one afternoon to wrestle with some physics features, diving into a messy mix of Blueprints and C++ scripts. It was one of those rare days where the logic just clicked. I was bouncing between visual scripting and code, testing ideas as fast as I could think of them.

When I finally snapped out of it, I looked at the clock and was genuinely shocked to see it was 7 PM. Four hours had evaporated. My coffee was cold, my stomach was growling, and I hadn’t moved an inch. But I didn't care. That session was my first real taste of the "Dev Flow". Because the engine responded instantly to my ideas, I never had to stop and wait. I was completely locked in, surfing that wave of productivity that I have since then been constantly chasing.

Moving through my second and third year of university, I started learning more about team management from a product owner / stakeholder point of view. In game development (and software engineering in general), developers are very aware of the fact that it takes about 15 to 20 minutes of intense focus to re-enter a complex mental model after an interruption. Team management in games is built around this fact; meetings are kept to a minimum and long 'focus hours' are blocked off to allow developers to remain in this deep focus state without interruptions.

Removing Blocks

However, as I noticed during Covid-19 induced lockdowns, guarding your calendar is only the beginning. Our university program slowly ramped up in speed, and during the end of the third year (during lockdowns) we were working on a 6 month project with a team of 16 developers. Bigger projects meant more assets, bigger Unreal Engine projects, and most importantly... bigger build times. Four hour focus blocks are great, but having to start off this focus block by recompiling the game's source code for over 30 minutes completely breaks productivity and flow.

These are the 'silent' blockers. A flaky test suite that fails randomly, a local environment that takes an hour to spin up, the "but it works fine on my machine" troubleshooting. These seemingly small moments force the developer to drop their mental focus and pick up annoying blocking issues.

For us, the biggest silent blocker was build times. Towards the end of our project, we needed to ramp up playtesting and often send new builds to our group of testers. This involved changing some test variables, making a development build, pushing it to steam and having the testers download the update. The entire process sounds fairly simple, but for us this took over 2 hours to complete.

If a player encountered a loading screen that lasted two hours, they would uninstall the game immediately. It kills the experience. Yet, as developers, we accepted this latency as "part of the job." We viewed these hours not as a system failure, but as a necessary evil.

Flow in Platform Engineering

This is where the mindset needed to shift. In the modern software landscape, Platform Engineering has emerged to solve exactly this problem. Its core philosophy is that the "developer experience" is just as critical as the user experience. If Game Design is about ensuring the player remains in a flow state, Platform Engineering is about the same for the developers.

My first experience with Platform Engineering started during my first trip to GDC 2022 in San Francisco. Right after the lockdowns, big companies were eager to show their newly built tools for developers. One of these companies was AWS, showing off their "Game Tech" cloud tools. They gave me a free AWS themed deck building game (BuilderCards) and subtly started my journey towards a proper platform engineer.

While the card game was a fun piece of swag, the actual tech demo is what stuck with me. Watching them provision game servers in seconds, which previously took me hours, was intriguing.

It wasn't just about the speed, but also about reliability. The "Game Tech" stack turned the chaotic process of deployment into a predictable, boring standard. That deck of cards sat on my desk for a long time as a reminder that there was a discipline dedicated entirely to solving the "silent blockers" I had grown to hate. It pushed me to look beyond just game design and start understanding the machinery that supports it.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Game Designers and Platform Engineers are two sides of the same coin. One builds for the player, optimizing for fun and immersion. The other builds for the developer, optimizing for speed and focus.

While the audiences differ, the mechanics are identical. A game designer iterates on level layout to ensure the player intuitively knows where to go; a platform engineer iterates on API design and CLI tools to ensure a developer intuitively knows how to deploy. In both cases, the enemy is shared: flow-inhibiting friction.

Whether it is a confusing level layout that causes a player to "rage quit," or a slow deployment pipeline that forces a developer to check their phone, anything that breaks the "flow loop" destroys value. In a business context, that lost value isn't just about frustrated employees; it is measured in lost velocity and the high cost of context switching.

This requires us to stop viewing internal infrastructure as a "necessary evil" or a secondary concern. By treating our platforms with the same care, polish, and user-centric design we treat our games, we ensure that the only challenge the developer faces is the code itself, not the tool used to ship it.